|

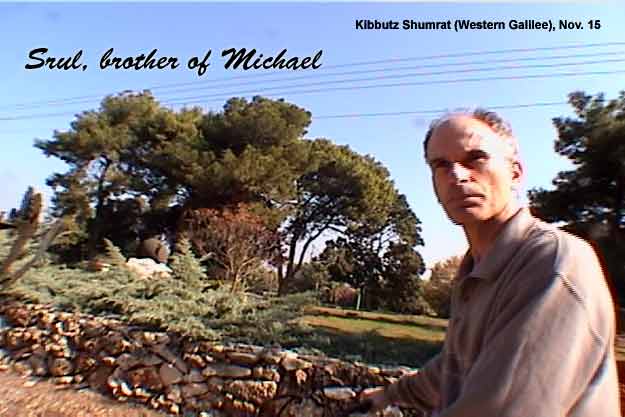

Srul Alexander, kibbutznik"Twenty-five years ago I would get up in the morning and milk cows, and I would think I'm bettering the situation of the kibbutz and the whole country. Now my focus is closer to home." They say every journey starts with one step. And every web starts with one strand. The web of friendship that is the basis of this project began with the strand from me to Srul. We got to Kibbutz Shumrat about 10 Friday morning and checked in to the guest room that had been reserved for us. Soon Srul rode up on his bicycle. I instantly felt that we had known each other for a long time.

Which, of course, we had. His brother Michael and I were friends in high school. We stayed in touch for a while, then lost contact and then resumed our friendship when we ran into each other about ten years ago. Now we get together every month or so for a hike (there we are at left). It was actually on one such hike, talking about Srul in Israel, that I first took a notion to visit Israel. Michael put us in touch, Srul invited me to visit, and planning commenced. So we had known each other, but not well, and I think if I had to pick him out of a crowd I could have, not because I remembered him but because he looks so much like his brother. We spent three days on the kibbutz. This first interview is our discussion as Srul showed me around for the first time. Transcription (edited) of video clips: Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3 • Part 4 • Part 5 • Part 6 Part 1 - Kibbutz population declining Peter: So you came about 30 years ago? Srul: Yes. In 1972. Peter: And your wife Ora, is she American, too? Srul: Canadian. She came a little before me. Peter: How many people live on this kibbutz? Srul: We have about 100-some families. I'd say a total population of about 400. Peter: Does everyboy know everybody. Srul: Of the permanent population, for sure. There are a lot of people nowadays who are not part of the permanent population. What we've done in recent years, we've started renting out rooms. We have a lot of people here who are not members. Peter: Because your population was declining? Srul: Yes Peter: People moving off the kibbutz, or out of Israel. Srul: Both. Most of the Americans left. Part 2 - Religion on the kibbutz and in Israel Peter: Is there a synagogue on the kibbutz? Srul: No. Peter: Almost nobody on the kibbutz would be religious? Srul: We have one person who became religious after his mother died. We're not anti-religious, but we're an a-religious society. Our affiliation is with the Social Democratic Party Peter: The social democratic party...is that different from the labor party? More left? Srul: Yes. A lot of people call it a socialist party. It used to be. More recently, the party aligned with some other non-socialist groups with similar views on how to solve the conflict, and issues like religious coersion, which is a very hot issue in this country. Peter: Is it still the case that there is no civil marriage in Israel. Srul: You can go to a lawyer, and write up a nuptial. But there is not civil marraige. Peter: So you and your wife were married in a religious ceremony even though you are not religious? Srul: Right. A small number of couples on the kibbutz simply didn't get married. Or some went out of the country to get married. A lot of people who have a problem... because of Jewish law. Say the woman is not considered Jewish, because her mother wasn't Jewish, even though her father was, so they have a problem getting married. One woman in that situation went through the process of conversion, but she regretted it after she had done it. Peter: Why? Srul: Because it was a meaningless farce. There are a number of issues regarding religious coersion in this country, with the whole population is forced to maintain a Jewish identity to the state. They say we're not like France or other countries. We're a Jewish state, meaning public transportation cannot run on Shabbas. What that means is that people with private transportation are ok...they can go to the beach on a Saturday afternoon if they want to. Part 3 - Kibbutz socialism Srul: Over here we have a dairy product fabricator...cheese, yogurt, milk. Peter: For consumption on the kibbutz or for sale? Srul: Mainly for our own consumption, but now we are going to expand it. We had a problem in the past. We have an exclusive deal of who we sell our milk to; the big coopertive of the whole country. We cannot sell milk to anyone but them, except for our own consumption. Meaning we couldn't make cheese, yogurt and such and sell them. Now we've made a couple of changes amd we're buying raw milk, and so we're able to make this into a real business. We've made a lot of changes on the kibbutz, and we are privatizing services. I don't mean that somebody owns it. It's still collectively owned, but it's not subsidized one hundred per cent. Up until now, a lot of services on the kibbutz were basically free, subsidized one hundred per cent. Laundry, dining room. You go and take what you want. If you don't eat it all, throw it out. Who cares? Peter: And who paid for the soap and stuff? Srul: We did. It was collective. When I was working before on the kibbutz, and now that I'm working off the kibbutz, all of my income would go to the kibbutz; I wouldn't see it. And I wouldn't get back in proportion to what I put in, but in proportion to what I needed. Peter:" From each according to his ability, to each according to his need?" Am I correct in saying that that's the kind of thing that drew you here into the kibbutz movement, more than any sort of Jewish identity? Srul: After living in this type of society for 30 years, I find a lot of flaws in it. I know that every system sows the seeds of its own destruction. And right now our system got to that point where the contradictions became greater than the positive aspects. One of the main problems, something specific to kibbutz socialism, is that we don't have any enforcement, no police force. The only way you motivate someone to pull his weight is public pressure. And some kibbutzim are better at applying public pressure, and some are less good. And Shumrat is one of them. It's never been a kibbutz where people wanted to get into conflict with each other. Let's say someone was expected to get up at 3 in the morning and milk, and he didn't get up until 4, well his co-worker might get mad at him, but there would never be anything officially done. (Over here is a monument to members killed in different battles, from the War of Liberation in '48, in '73, in the October war, and around that time we lost another member on a training exercise.) Part 4 - Land, conflict and history Peter: What was this land in 1948 before you guys started the kibbutz? Srul: There are a couple of buildings built by a group of German Christian settlers, called Templars, at the beginning of the century. In Jerusalem and in Haifa there are two quarters, called the German Quarter, where the Templars lived. They sided with the Nazis in World War II. They are no longer here. There wasn't an Arab village here, but there was a village nearby with a similar name. In '48 - the Arabs call it "nachva" that's like holocaust in Arabic. What happened is that they were all forced to leave. I try to be as objective and neutral as possible when I look at historical events. The two sides that I know: The official Israeli side is that the reason there are Arab refugees is that the Arab forces told the inhabitants of this area, "Clear out, and we'll purify the area, and you can come back. Peter: Although I understand that this is no longer the main line in Jewish historiography. Srul: I don't know.; I don't have any facts that would dispute that. I'm sure there is a lot of truth in it. I also know that here was an attempt to frighten to frighten the civilians. They weren't targeted, but they were frightened by the Haganah, the Palmach, and particularly the underground right wing groups. And they wanted to clear the area of Arabs. And I'm sure they did what they could to accomplish that. But it wasn't the main event. These were more or less exceptions. Part 5 - More on land, conflict and history Srul: There is definitely a discriminatory approach to allocating land. It's a problem, and it won't be solved unless we solve the whole conflict. It's a serious problem. It's one of these issues that I find hard to imagine we will be able to bridge. We have a demographic problem. If we want to remain a democratic country, and the Palestinians who are living here and in the Occupied Territories, their birthrate is the highest in the world. And the time will come when we will be overthrown democratically. Peter: So it's hard to see how you can remain both a Jewish state and a democratic state. Srul: Exactly. It's a very difficult problem, and anyone who says he has a solution, if you ask me, is being overly simplistic. What I believed in in the past was a bi-national state, one state that would meet the needs of both people. You need a heightened level of trust to have something like that. Maybe the chief of staff would be an Arab, and the prime minister a Jew and the minister of defense would be an Arab. I can't see something like that happening in this situation. So there has to be a two-state solution. It's possible that Jews could remain in their settlements in the Occupied Territories if they would accept Palestinian sovereignty. And the same would apply to Arabs living here. A lot of the Arabs are moderate. They want to make a living. Not easy for a lot of them. Unemployment in the Arab sector is very high. The means of production, like land, we're back to that issue. It's a problem. What makes it even worse is that many of the enterprising Arabs, the professional Arabs do not go back and help their communities as much as should be. Part 6 - More on kibbutz socialism, family life Srul: This is a furniture factory. It's also gone through a transition. We had one of the main names for furniture in the country. If you say to somebody "Shumrat," they say "Ah, Shumrat furniture." But we've finished. Ayear or so ago we rented out the space and the equipment to another furniture company. But they're terminating their contract with us, and we have to figure out something to do with this building and equipment. And it's too bad. It was a nice source of income. Peter: Why did you abandon the factory? Srul: We were losing money. When this was a textile factory and I worked there, I had a lot of conflict with some of the people, the general manager. My approach was that good business policy was to try to find fair solutions to relating to customerssuppliers and workers, and they said you're not looking out for your own interest. You're a socialist! Maybe I am, but I still think that looking for fair solutions is the best way. Anyway, what I was saying before about the idea of exploitation by paying you $25 for something that I'm getting a surplus of $75, don't think that's a definition of exploitation. Why? Because I'm taking a risk. I don't know if I'm going to succeed in selling it for $200. I feel obliged to give you a fair salary. And if $25 is fair because you put in two hours of work on it, and that's the going wage, then that for me is fair. That you can call "social democracy," not "socialism." That's why I consider myself as more of a social democrat. I see that publicly-owned means of production and supply are very problematic. Especially in an age like now, when we are not motivated by ideology. Maybe 25 years ago I would get up in the morning and milk cows, and I would think I'm bettering the situation of the kibbutz and the whole country. Now my focus is closer to home. My daughter is at Haifa University, and we have to put her through school.She got out of the arjmy a year ago, and she didn't find work. With what we have after our heavy tax, we have to pay her tuition, rent, etc. It's not easy, even though Ara (a dental hygienist)and I earn decent salaries. Tamir, my oldest son, is planning to go to school in a year. He's probably going to be pretty independent. Peter: Your youngest son has his own apartment as well? Srul: He has a room in our house, and he also has a room with his 12th grade friends at another place on the kibbutz. It's run like a mini-kibbutz. They have to do a bit of work to raise a bit of money, to pay for teir rent and their needs and whatever. Peter: When you're children were little, did they live with you? Srul: Up until 10 years ago, they slept in their childrens' houses. And 12 years ago, coincidentally at the time of the Gulf War, it was good timing. The kids were all at home already. It was a lot easy to handle things when we had a shelling. Peter: Did you have incoming scud missiles in this area? Srul: Yes. Just in the beginning. Before the war started I was called up as a medic. And I remember that the night the war started, when the first scuds were falling in the Haifa area, we were in formation, ready to move to that area The whole issue of where the children slept did not begin ideologically. It began practically, a practical solution to the problem of room space, limited resources. It became an ideology. There were a lot of "advantages." But I think it didn't do a lot of damage. there were problems. But the idea in the beginning was just a practical solution to limited resources. Also, it offerred a couple of other solutions. Particularly, after the holocaust, it saved a number of orphans from feeling left out. Another thing from that era was that parents were not called "mommy" and "daddy," they were called by their names. Another thing that made life easier for orphans. The question is, what type of ties were there between parents and children, or between siblings. There definitely was an organized arrangement for family time. It was less, but it was more quality time. When we were raising children until 10 years ago, 4 o'clock until 7 o'clock, the kids were home. Work for me ended for me at 4 pm. If I had extra work to do, I would go back after dinner. But between 4 and 7, we were basically a family, and it was quality time. We didn't have to make meals; we ate in the dining room. We didn't have to do laundry. In that era, there were a number of professionals from outside the kibbutz who came and joined, because they said we don't have time to give the same quality time to our kids.This is the best way that we can bring them up. So there were advantages. There were problems, too, like everything.

|

HOME

BIBLIOGRAPHY

LINKS

Going to

Israel

What Michael thinks

What Peter thinks

Video Notes

Guest Book

TEL AVIV

Nov. 10-13

- Capt. Dan Tamir

- David Rubin

- Serge Samuel

- Abraham Huli

- Col. Yoash Tsiddon - Chatto

- Ronen Zadoc

- Joshua Shushun

- Ran HaCohen

WESTERN GALILEE

Nov. 14-17

- Elias Chacour

- Srul Alexander

- Mark Erlank

- Aqueduct

- Yehuda Benin

- Acco

- Yaacov and Chaya Oren

- Dr. Nasser Gadban

- Safi

JERUSALEM & RAMALLAH

Nov. 18-23

- Elana Rappaport Schachter

- Tova Saul

- Talal

- Sam Bahour

- Dr. Mustafa Barghouti

- Keren Mulag

- Arak Kilemnic

- Jeff Halper

- Shabbot dinner

- Sami Taha

TEL AVIV -

Nov. 24

- Tel Aviv restaurant owners

- David Libon

- Grazia